The Practice of slavery was abolished in Argentina in the year 1853. Although, in 1813, the freedom of newborn slaves and all enslaved people who set foot on Argentine soil was decreed, the abolition of slavery was only declared in the Argentine Constitution of 1853 and was implemented in the province of Buenos Aires after 1861.

However, this did not change the fortunes of the Afro-Argentines, as it only brought further suffering to them. Argentina’s leaders, who were mostly Spanish businessmen, stressed the importance of modernizing Argentina and citing Europe as the birthplace of civilization and progress.

Their thoughts were akin to those held by other predominantly white European nations during that era, who believed that anything pertaining to white signified advancement, whereas anything pertaining to dark skin was considered retrogression. The Spanish colonists believed that Argentina would have to physically, mentally and culturally destroy its Black population to join the ranks of other advanced nations like Germany, France, and England.

The Spanish colonists decided to implement severe economic policies and practices that would result in the disadvantage or loss of predominantly black afro-argentines men.

When Argentina was confronted with the prospect of becoming involved in the most bloody interstate conflict in Latin American history, commonly referred to as the Paraguayan war of the triple alliance, a significant number of afro-argentines were dispatched to fight.

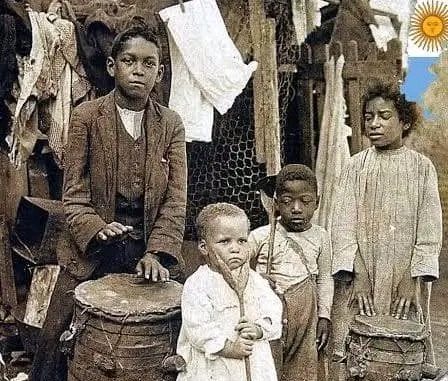

Unfortunately, thousands of Afro-Argentines died in this war because most of them had very little military training. Other severe circumstances imposed by the Spanish colonists on the afro-argentines included systemic controlled poverty, unfavourable government policies aimed at marginalizing them, elevated infant mortality rates, and a limited number of married couples within their ethnic group. Due to the discriminatory treatment they were subjected to, a significant number of Afro-Argentines were forced to flee their homeland and relocate to Uruguay.

Those who remained in Argentina were faced with the challenge of battling the cholera epidemics in 1861 and 1864, as well as the yellow fever epidemic in 1871, in what many refer to as a biological weapon to eradicate the afro-argentines population. These tragic events resulted in a substantial decline and a significant exodus of Afro-Argentinians from Argentina to other parts of South America, or, regrettably, to their demise.

The barbaric act was not limited to Argentina, but also included its neighbouring countries. Particularly, Brazil, Cuba, Columbia, and other Latin American nations attempted to eradicate or marginalize their black population and usher in a steady stream of European immigrants. The uniqueness of Argentina’s story is due to its success in establishing and rebranding its image as a predominantly white country.

When the Spanish-controlled Argentine government realized that the country was experiencing a significant decline in population due to its expulsion of the Afro-Argentine population, they devised a plan to open its borders to anyone of European descent living abroad. The goal was to attract other white people from other parts of the world to live and work in Argentina with additional incentives. One of the strongest incentives was the promise of citizenship and social assistance benefits.

Juan Bautista Alberdi, an Argentine political theorist and diplomat, who was probably best known for his saying “to govern is to populate,” played a big role in encouraging White European immigration to Argentina in the 1850s. Alberdi’s concepts were enthusiastically embraced by the then-president of Argentina, Justo José de Urquiza, who incorporated them into the first constitution of the nation.

this amendment resulted in influx of white settlers from Spain, Italy, Germany, France, and Belgium.

This marked the onset of the decline of the Afro-Argentine population and the establishment of Argentina as a nation dominated by whites. This is Argentina as you see it now.

One of the founding fathers of the apartheid policies against the Afro-Argentines was Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who was an Argentine activist, intellectual, writer, and statesman at that time. Later, he became the seventh president of Argentina, which made it easier for Argentina to set up an all-white apartheid system. Furthermore, he resisted racial equality and was a prominent advocate for Argentina’s transformation into a nation more akin to Europe than African or Amerindian.

Sarmiento was quoted as saying that: “Twenty years hence, it will be necessary to travel to Brazil to see Blacks.” Although he was aware of the existence of Black Argentines long before the majority of white settlers arrived, he suggested that the country would struggle to recognize them for a long time.

Sarmiento was accountable for the economic and other forms of genocide that decimated the Afro-Argentinian population, resulting in a small population of black Argentinians during the early 1900s. Under Sarmiento’s watch, the Argentine government ignored calls for inclusion of Afro-Argentinians in the national population census. His apartheid policies included the separation of blacks from Europeans and the placement of blacks in abandoned communities with few medical facilities. It was the Sarmiento government who deliberately halted medical treatment for the Afro-Argentines, when cholera was prevalent, leading to the deaths of many afro-argentines, mostly males.

Sarmiento was also responsible for the mass imprisonment and extrajudicial murder of Afro-Argentinean men. Black Argentine men were punished with a harsher penalty for any crime they committed than European men. This was similar to the practice that was created during the Jim Crow era in America, which involved locking up black males to mentally destroy black families. Regrettably, this discriminatory behaviour severely impacted the Afro-Argentinean women, leaving them with little choice but to have children with white-European settlers.

Because of years of racial apartheid policies, black afro-argentines women who had children with white settlers were forced to either pass as white or Amerindian to get the benefits of whiteness for their children and themselves. Many black women in Argentina had to use laws to improve their lives. Black afro-argentine women were subjected to an oppressive regime that dictated their well-being and that of their children.

As time passed, Sarmiento’s political activities and outspokenness caused the military dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas to exile him to Chile in 1840. While in exile in Chile, Domingo Sarmiento made a damning statement against the Afro-Argentines, and I quote him:

“We must be reasonable with the Spaniards,” he wrote, “by exterminating a savage people whose territory they were going to occupy, they merely achieved what all civilized people have done with savages, what colonization did consciously or unconsciously: absorb, destroy and exterminate.”

The economic downturn compelled many Blacks and mulattos in Argentina to seek alternative statuses beyond that of black, provided that they could settle into more ambiguous racial and ethnic categories. This resulted in the creation of a third race, a eugenic practice that Europeans propagated throughout the countries they colonized, with South Africa serving as a notable illustration.

Unfortunately, these categories were morphed into criollo (a pre-immigrant background often associated with Spanish or Amerindian ancestry), morocho (tan coloured like), and pardo (brown skin coloured). Many Afro-Argentines dissociated themselves from their blackness at a time when that was a state requirement, even though they eventually saw them as “others.”

The issue was so bad that even Carlos Saúl Menem, the former president of Argentina, found it easy to incorrectly state that blacks do not exist in Argentina and that this is a Brazilian issue.

Many false historical books in Argentinian schools went on to erase the history of Afro-Argentinians, who were once the true inhabitants of the land and throughout South America, supporting Carlos Menem’s illegitimate claim.

Even when their first-ever president, Bernardino de la Trinidad González Rivadavia, was an afro-argentine, modern-day Argentina continued to deny the impact of the Afro-Argentines. Bernardino was said to have a dark appearance because of his African background. He was later honoured as a respected captain-general. His remains are buried today in a mausoleum on Plaza Miserere, next to Rivadavia Avenue, which is named after him.

Afro-Argentines are very alive and surviving in Argentina, but unfortunately, the current image of Argentina does not reflect their presence. Today, there is still a large Afro-Argentine community in the Buenos Aires districts of San Telmo and La Boca.

Argentina’s football team, considered one of the world most cherished national teams and Argentinians finest, embodies the essence of modern Argentina, sporting a look that reflects their apartheid past. Despite the existence of Afro-Argentinians, the national football team still features players of European descent<<Continue Reading>>>

Leave a Reply